When Civic Duty and Family Legacy Meet at the Polls

Guest Post by Marguerite Kearns (SUNY Press Author)

My grandfather Wilmer Kearns made a face when I was ten years old and he told me how some supporters of women’s voting rights weren’t considered deserving of recognition because a few made decisions and took action criticized by later generations. Many of these early women’s rights activists were labeled as old fashioned, stiff, ugly, and dull. Tens of thousands of women campaigners across the nation were painted with a single label and it wasn’t complementary. This bothered me at a young age. I wasn’t sure what to do.

I imagined Granddaddy as a young man, standing straight with his thick dark hair brushing against his forehead. Even at the age of ten, I found my grandfather handsome. After moving to Woodstock, New York in my late twenties, I noticed how his shoulders slumped and his arthritis had grown worse. He remained an essential link for me—someone able to tie the tales of successive waves of protest together into a narrative loaded with force and momentum. So decades later, I wrote a book.

“Your grandmother Edna trusted in justice and did the best she could. Organizing in one’s hometown on Long Island was tough. But sometimes, exciting things happened, like when the African-American pastor in our hometown, Reverend Dudley, joined the coalition and spoke at a suffrage rally. My precious Edna was always on the go,” Granddaddy said. Edna didn’t bubble over with small talk. When she put her voice into action, Edna pulled off a self confidence that at a young age I could only envy.

Edna Buckman Kearns, circa 1915, with her phone that she used for voting rights advocacy.

Granddaddy had a job in a cigar factory on the Lower East side of New York City. They lived in a Quaker boarding house, the Pennington, until they could afford their own home in Rockville Centre on Long Island. My grandmother’s activist generation in the city and the country consisted of those who communicated opposition in addition to words. The lifting of Edna’s eyebrows spoke volumes, in addition to her intense eyes and delicate stature, according to my grandfather. Edna was anxious to march into the unknown and make the best of it. She shoved petitions in front of stranger’s faces. She marched in parades, spoke before groups, visited elected representatives, and wasn’t intimidated by the opposition. She created a substantial history of grassroots organizing herself before asking others to join her. She believed in the equality of all living forms.

Granddaddy said many women’s rights activists didn’t mind working for the right to vote from state to state—an agonizing, exhausting, and lengthy process. Many predicted that women would be under the thumb of patriarchy for a hundred years or more if more women didn’t put their bodies on the line and have voting rights guaranteed in the US Constitution. My grandmother Edna wasn’t well known. I think she was happiest when she convinced others to take action. Sometimes I show Edna’s original telephone to audiences who want to hear her story. Edna used the phone to smile and dial in order to rally support for women’s right to vote.

Sometimes Granddaddy’s stories told to me came straight from history books, sometimes from memory and imagination. His factual accounts featured women like my grandmother who practiced communication skills as they hit the ground running to agitate during the second decade of the 20th century. Edna perfected persuasive arguments; spoke in public; networked; wrote newspaper columns; organized on local, state, and national levels; and sang in a loud and clear voice during suffrage parades.

She didn’t draw undue attention to herself. If New York attorney Inez Milholland rode on a horse in the front of a votes for women parade, Edna found her place in the rear, just as significant as the front or middle. She marched wearing her Quaker bonnet in suffrage parades. In New York City and on Long Island, she was comfortable standing up for the right of women to vote in local, state, and national elections. In their own deliberations, Quakers didn’t vote but rather reached unity on decision making through a spiritually-engaged process. It remained urgent, Wilmer said she believed, that all American women have the right to vote in their communities, states, and the nation.

I shook myself like a soaked dog and asked Granddaddy how Edna felt when faced with the odds of a million to one to win a state suffrage referendum or other campaign, especially the passage and ratification of an amendment to the US Constitution. What he told me made me realize the power of Edna’s optimism and that of her generation. By my childhood, their voices had been hidden and dismissed. I experienced Granddaddy as an open storyteller and listener, someone missing his late wife and serving as a bridge when passing stories on to my generation—even if I couldn’t fully appreciate these tales when I first heard them.

Without my grandfather, and later my mother Wilma, I wouldn’t have been able to understand this final stage of the early women’s rights movement. I wouldn’t have understood its limitations and accomplishments or the lessons that later generations would be able to learn from, adapt as effective strategies and tactics, while putting other aspects of the campaigning to rest.

Edna Buckman encouraged Wilmer Kearns to rearrange his priorities in 1903. She loved him. He loved and treasured her. They married in 1904. I popped an oatmeal cookie into my mouth and kept a straight face at age ten when concentrating on what Granddaddy had to tell me about their lives together. Then I brushed cookie crumbs from my lips, sat straighter in my chair, and waited for another round of suffrage stories.

My mother resisted the arrival of a black and white television set in our house before I celebrated my tenth birthday, so I hadn’t lost the ability to transfer Granddaddy’s stories from the spoken word to images spreading across my eyelids’ interiors. I longed to know more about Edna’s hands, fingers, eyebrows, and lashes than what I’d seen in photos. I pictured how she may have spoken to Wilmer from across a table at the Market Street teahouse in center city Philadelphia after they met. Edna delicately cradled her teacup and closed her eyes for several seconds before speaking, my grandfather told me, just as I modeled her actions with a cup of grape Kool-Aid and a peanut butter cookie. Naturally I couldn’t pull off these actions. I was too young.

Granddaddy didn’t overload me with detail or description. He stood aside and expected me to take charge when imagining what Edna wore to art school, to Quaker worship, to women’s rights events. From where I listened on a chair in Wilmer’s kitchen, Edna was memorable because of her carefully chosen words, particularly when she flipped the sash of her Quaker bonnet aside and spoke boldly about how women must stand up for themselves.

Edna told Wilmer: “Even if we win, my friend Bess predicts that a constitutional amendment will only shake things up a little. The uproar will settle, many women will vote, and then everything will shift back to men on top again, with women volunteering as poll watchers and complaining about corrupt and manipulated elections.” Edna’s best friend, Bess, believed Mother Jones and Emma Goldman were right. Women should go for the jugular, not pretty please their way to Washington, DC. Bess said, “New thinkers today are anxious to do away with a top to bottom social structure. They protest wearing fancy gowns over the same old filthy petticoats.”

Granddaddy told me he had to work double time to understand women’s issues before volunteering as an ally. He steered me back to the tale of him as a young man, waiting for a stein of golden beer to arrive at his restaurant table on the Lower East Side in 1902. He lit a five-cent cigar. He’d have to stop drinking beer and smoking cigars if he ever became serious about deepening his relationship with Edna. He’d heard about the 1848 women’s convention in Seneca Falls, New York and how it had turned into another stop on a metaphorical underground railroad in support of more layers of commitment and effort. This was added to a long-standing effort by a diversity of men and women activists in New York City supporting equal rights.

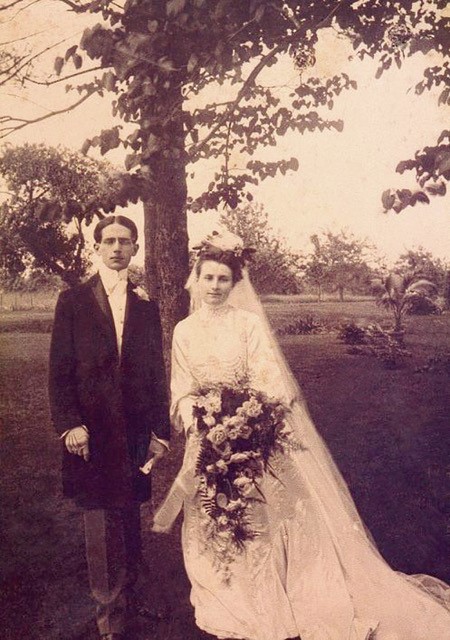

1904 wedding photo, Wilmer Kearns and Edna Buckman.

My grandfather thought about and dreamed of freedom and equality from almost the start, back when the thirteen colonies on the East coast rebelled under the rule of England. Abigail Adams lobbied her husband John in a letter to “remember the ladies.” Women served as the backbone of boycotts of tea and other taxable goods in the early days of the American Revolution. Many operated family farms after the men marched off with the independence forces. Some women refused to pay taxes without voting and political representation. A significant number petitioned elected officials repeatedly over the generations for equal rights, especially before and after the Civil War.

My grandfather kept a cigar stub resting in an ashtray in his kitchen when I was ten and making regular visits to see him. Granddaddy lit the cigar, blew smoke into the air and sighed. It took special effort for him to tell me about the history of resistance. A significant number of women in Bess and Edna’s generation petitioned men in power. They protested at the Statue of Liberty’s unveiling in New York City’s harbor. They vented when lecturing from soapboxes. They recruited allies. They joined forces. Most were volunteers who had little formal educations. Some woman activists collaborated with dissenters, labor organizations, ethnic working women, women of color. They organized separately and together. They marched, rallied, raised funds, and stood up against fierce opposition, including outraged and angry individuals and organizations in alliance with the liquor industry.

U.S. women asked men like my grandfather Wilmer Kearns to march with them in suffrage parades and endured criticism and humiliation from those known as “antis.” This constituency opposed to women voting included both men and women. Outrageous predictions of dreadful outcomes if women voted filled empty spaces in opposing leaflets, speeches, and satiric content. Wilmer joined the men’s division during women’s marches and stood next to his wife Edna during her street soapbox presentations in New York City, some of them ongoing for hours until my grandmother Edna could no longer utter another word.

I listened to all of this and absorbed as much of Granddaddy’s descriptions as possible as more images of my grandmother and other activists accumulated behind my eyelids. I imagined Wilmer struggling to face colleagues at his office at the cigar manufacturing firm after the word got out that he’d joined a line of men suffrage marchers down Fifth Avenue in New York City. I heard more about Bess, my grandmother’s best friend, her vulnerable and innocent nature, as well as how she refused to marry if women were treated as second-class citizens. Later in life, I voted every chance I was given. I could do no less.

Marguerite Kearns grew up in the Philadelphia area learning about her family history. A former journalist and teacher, her award-winning writing has contributed to a support base for her storytelling. She lives in Northern New Mexico.