Wearing Our Crowns

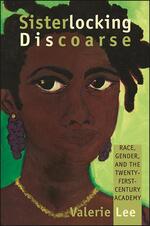

Guest Post by Valerie Lee (SUNY Press Author)

When I wrote Sisterlocking Discoarse: Race, Gender, And the Twenty-First-Century Academy, I thought that I was sharing a story of yore—how a Black woman now in her seventies juggled administrative tasks while conscious of the fact that her head had the only coiled, twisted, braided hair in various C-suites. I thought that I would have to explain that heretofore, Black hair had been deemed unprofessional. Surely, times have changed, and there is enough evidence on movie screens and football fields to support transformative thinking about what constitutes acceptable beauty aesthetics, more specifically professional taste. Currently, I watch Black women newscasters rock locs and knots, braids and beads. I see Snoop Dogg wearing braids so long he can sit on them; I cheer as I see NFL players with sweaty, kinky hair score touchdowns. Former quarterback Colin Kaepernick’s knee posture was probably exacerbated by the crowning glory on his head that waved in the wind—an Afro that dared form a halo.

Given these changes, I did not know how many readers would remember an era where various physical parts of Black bodies, from lips to hips, were denigrated. Before dismissing my own battles with hair politics as dated, I should have been paying attention to an undercurrent—the laughter and embarrassment that some even in Black communities felt when gymnast Gabby Douglas and Simone Biles won their many medals. When Gabby’s and Simone’s athleticism affected the smoothness, slickness of their coiffures, some sistas asked, “Why don’t they straighten, perm, or fix their hair?” Apparently, it is not enough to hold a golden crown in one’s hands if the crown on one’s head does not look golden. Moreover, there have been critiques of the hair texture of Blue Ivy, the wealthy, adorable, talented child of superstars Beyoncé and Jay-Z. The vexed nature of Black hair politics keeps rearing its head.

Shortly after I finished my book that uses the history and progression of hair politics as its opening metaphor for leadership journeys, Congress passed the CROWN Act of 2020. Who would have thought that such an Act would be needed in the 21st century? Cleverly, CROWN stands for “Create a Respectful and Open Workplace for Natural Hair.” Many thought that Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 protection against Afros had done the job of allowing people of color to have the same hair privilege as their white counterparts: Hair that grows out of one’s scalp is one’s natural bounty. Yet, there has continued to be so much discrimination against “Black hairstyles” that states on the west and east coasts have subsequently passed CROWN Acts. States in the Midwest and South have been more timid, leaving such Acts to those cities where there are diverse populations. In 2021 my midwestern city, Columbus, Ohio, passed a CROWN Act, adding provisions to its City Code forbidding discrimination against “cultural hairstyles” (braids, locs, cornrows, bantu knots, afros, and twists). According to the 2021 Dove CROWN Research Study for Girls (500 Black and 500 white), “100% of Black elementary school girls in majority-white schools who report experiencing hair discrimination state they experience the discrimination by the age of 10”(see https://www.thecrownact.com/about). How long do these ten-year-olds carry self-esteem issues? How have the ten-year-old memories of the Michelle Obamas and Oprah Winfreys of Black America affected their leadership and presentation styles?

The continuing discrimination involving the politics of hair takes me back to the gospel song, “I Shall Wear a Crown Someday” with lyrics that mandate one should “Tell the Story how I made it over.” Although Thomas Whitfield’s lyrics are speaking of a heavenly home where a crown is given to those who have suffered oppressions, social justice first requires some work in earthly spaces where one’s natural-born crown is accepted and can be worn. One of those spaces is higher education. Despite its emphases on catch phrases (e.g., “inclusive excellence”), higher education struggles to understand the daily journeys, histories, and values of persons formerly not permitted in its hallowed halls. Understanding diverse groups must go beyond what I call the prose of diversity (definitions; demographics; demands) to the poetry of diversity (the everyday stories of what each person brings to the human narrative). That’s the work I do in Sisterlocking Discoarse, from the hair politics pun in its title to the behind-the-scenes observations that untangle all that is knotty and nappy in racialized and gendered institutionalized spaces.

Valerie Lee is Professor Emerita of English at The Ohio State University. She is the author of Sisterlocking Discoarse: Race, Gender, and the Twenty-First-Century Academy with SUNY Press, Granny Midwives and Black Women Writers: Double-Dutched Readings, and is the editor of The Prentice Hall Anthology of African American Women's Literature.