Celebrating Du Bois’s Birthday and Committing to the Souls of Others

Guest post by Erika Renée Williams

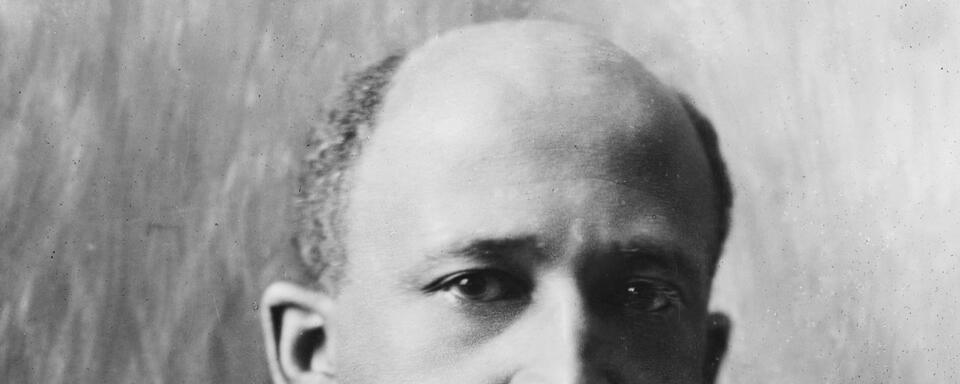

In the opening chapter of The Souls of Black Folk (1903), William Edward Burghardt Du Bois recalls the watershed moment when he first understood that, by the dictates of U.S. racism, he was deemed “a problem” by his white compatriots. For the most part, Du Bois was joyful as he came of age amidst the purple hills of Great Barrington, Massachusetts. But one fateful day, in a “wee, wooden schoolhouse,” as Du Bois participated in an exchange of “gorgeous visiting cards” between the boys and the girls that were his classmates, one girl, “a tall newcomer,” refused his gift—and thereby, his affections—with a scornful glance. The philosopher George Yancy suggests that the young white girl’s rejection of Du Bois amounts to his body being stolen away, but I believe that his soul was perhaps the most diminished by her unkind act. For a soul stricken by racism is unable to fully flourish, its wingspan clipped by the psychic cruelty and material violence of social exclusion. Characterizing this personal story as paradigmatic of Black American experience, Du Bois defines the state of being that overtook him as double consciousness, a condition in which “…the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil and gifted with second-sight in this American world, a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul against the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. One ever feels his two-ness, an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.” Rejected and alienated by someone with whom he sought an intimate connection, Du Bois was tasked with picking up the pieces of both his body and his soul—trying to render whole what had been cleft in twain.

As I argue in my book Tales from Du Bois: The Queer Intimacy of Cross-Caste Romance, Du Bois implicitly presents double consciousness as the consequence of a failed cross-caste romance, an exercise in irony, since the Euro-American directive that Black folk worship at the altar of whiteness is paradoxically foreclosed at the possibility of interracial intimacy – either in the form of friendship or romantic love. Indeed, in his 1969 autobiography, Du Bois reveals that his story took place when he was a teenager, whose more mature intentions likely included the frisson of eros as well as the intimation of social equality. His tale of woe is thus of the “tall” variety, and his recasting of its elements indicates an acute awareness of the firmly entrenched taboo against miscegenation in the United States. As I argue in my book, Du Bois’s personal story as narrated in Souls is the inauguration of what I call the trope of “cross-caste romance,” the “interplay of heightened awareness of and desire for another effected across stark lines of purportedly immutable yet socially constructed difference-rendered-as-status” that proliferates throughout his fiction. It thus marks Du Bois’s participation in a literary tradition of romantic nationalism in which intimate relations between persons separated by racial, class, and caste differences are deployed to consider the possibilities and failures of pluralism as a strategy for unifying the nation. The failure to bring the marginalized into the cradle of the nation, is, for Du Bois, the failure of both U.S. democracy and nationalism writ large. Such moral and political failures echo in many of Du Bois’s writings – in the short story from Souls, “Of the Coming of John,” when John is expelled from a music hall and thus denied both the aesthetic transport and cultural provocation of Wagner’s Lohengrin; in the little-known detective stories from Horizon magazine that feature a Black Pullman porter who protests his false identification as a criminal by becoming a detective and thus, the very instrument of justice; in the allegorical fairytale from Darkwater “The Princess of the Hither Isles,” in which an isolated mixed-race princess refuses to trade her land and body for marriage to a white imperialist king; and in the modernist novel Dark Princess, in which the romance and shared political radicalism of a Black expatriate politician and a South Asian princess succeed in unseating the preeminence of the European world, flouting caste boundaries, imperial logics, and nationalist origin stories alike.

Like the protagonists of his fictional works, Du Bois’s response to having his body and soul diminished was multiple and contradictory. On the one hand, he laid claim to the American body politic – however hostile. Yet on the other hand, he transcended the boundaries of the nation, engaging in a process of self-love and Black reclamation that I characterize as queer since it is auto-genetic and auto-erotic in quality. By absenting himself from the United States and seeking refuge in Germany as a graduate student at the University of Berlin, Du Bois found the perfect opportunity to leave the nation behind, to journey further within himself, and to turn a critical eye on American misanthropy and xenophobia.

On the 23rd day of February in the year 1893, while ensconced in his adopted home of Berlin, Germany, William Edward Burghardt Du Bois celebrated the occasion of his twenty-fifth birthday by following closely a program that he had sketched for the day. His planned itinerary, which recalls the memoirs of Ben Franklin in its attention to detail and equal commitment to both discipline and pleasure, included a good share of aesthetic appreciation (inclusive of music, poetry, and art), epistolary communication, and culinary indulgence (his “supper” consisted of a decadent combination of Greek wine, cocoa, oranges, and “Kuchen” (cake). Yet what most stands out in Du Bois’s program is his praxis of self-examination. For in his chosen land, “where the heart of my childhood loosed from the hard iron hands of America,” Du Bois experienced a freedom that, as he relates, he had only heretofore felt as a baby. No longer a “problem,” he was poised to become “a co-worker in the kingdom of culture” and moreover, a man free to fashion from his wounded heart an ethics of universal parity.

For while there were pointed moments of casual sociality (cross-cultural and interracial) on his birthday – a midday “dinner” with a friend and the spying of a “pretty” German girl over an afternoon coffee in Potsdam, for the most part, Du Bois’s day was marked by the rhythm of solitary introspection through moments of prayer, song, and reverie, all designed to elicit in him a thorough accounting of his principles, his values, and the consequences of his ambition. For, in spite of his intention to “strive,” adopting the rallying cry of “Carpe Diem!” as his motto, Du Bois was compelled to reflect upon the extent to which his own “best development” might impinge upon the parallel development of others: “I am striving to make my life all that life may be—and I am limiting that strife only in so far as that strife is incompatible with others of my brothers and sisters making their lives similar.” “The crucial question,” Du Bois concludes, “…is where that limit comes.” How does one balance the needs and desires of oneself with a Levinasian duty to heed the needs and desires of the other? Du Bois acknowledged regret over his role in the “life-ruin” of a German shop-girl Amalie, deriding his action as “cruel.” Nevertheless, he insisted that his own best development could be commensurate with that of the wider world and more pointedly, that the rise of the “Negro people” would usher in the rise of the world. To bring about this universal edification – to see that the distinct notes of beauty, truth, and goodness be merged into one harmonious chord, Du Bois pledged that he was willing to “sacrifice” and even, in his 1895 essay concerning the legacy of Jefferson Davis, to “submit” to the cause of the greater good (contra the brutalism of the Confederate soldier). Drawing out Du Bois’s beliefs to their logical conclusions, I say that the rise of the vulnerable, the marginalized, and the oppressed must predate and presuppose the best development and rise of the larger and often, dominating, echelons of the world. In other words: without justice, there can be no peace.

“How does it feel to be a problem?” W. E. B. Du Bois opined. Today, in a world in which voter suppression is reprised with a vengeance; in which reproductive rights are rescinded; in which Black, BIPOC, and queer folk – no matter how educated, industrious, or illustrious – still live at the precipice of expulsion; in which African American history is besmirched and outlawed; in which gender inclusive language is mocked and banned; and in which gender affirming care for transgender youth and adults of all colors, castes, and nationalities is dismantled and criminalized, I hear the call of Du Bois, who instructs us to be both in and above the politics of the nation and to disrupt the common practices of “the Zeitgeist.” In this spirit, I marshal Du Bois’s ethics, forged in Great Barrington, emboldened at educational institutions like Fisk, Harvard, and the University of Berlin, and consecrated on his birthday, to protest the ongoing litany of outrageous threats to U.S. democracy and moreover, to the very arc of justice. In her poem “Mulberry Fields,” the poet Lucille Clifton cautions us that “at the masters table only one plate is set for supper.” Anticipating Clifton, Du Bois reminded us that to measure one’s rise against the potential fall of another and to work together, “giv [ing] each to each” what we “so sadly lack,” would nourish us all. Put simply, we must be as resolute in protecting our own souls as we are fiercely and fearlessly responsive to the souls of others.

Erika Renée Williams is Associate Professor of English and Africana Studies at the University of Connecticut.