Immanence and Transcendence

Guest post by Deborah Justice

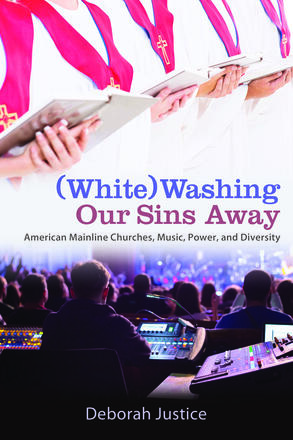

One of the main assumptions that people tend to make about music—both the religious music that I study and music in general—is that younger people like louder, amp-ed, fast music and old people like slow, quitter, acoustic music. This can often be true for individuals, but the actual sonic situation is more complex. In this edited selection from (White)Washing Our Sins Away, I talk about how this false correlation of age to musical preference played out in many American churches around the turn-of-the-millennium.

*******

*******

As mainline Protestants began incorporating amplified, guitar-based Contemporary worship music in an attempt to retain cultural relevance, they negotiated specific pragmatic questions: what instruments to use, what to sing, how to sing it? Contemporary worship brought in elements from beyond mainline Protestantism’s historical limits. These sonic elements carried potential overtones of changing social and sacred identities. Looking at their own demographics, mainline Protestants knew that their institutions needed to make some changes, but how much change and diversity was too much? Would incorporating elements like guitars and Contemporary evangelical repertoire result in identity-compromising social and theological shifts? Could mainline Protestants retain core features and values while retaining (or perhaps reclaiming) relevance in America’s shifting religious landscape?

The ways in which mainline Protestants answered the three sonic questions--What instruments to play? What music to play and sing? How to sing it?—depended on how they wanted worship services to relate to the rest of their lives. On both musical and theological levels, to what extent should “Sunday morning” exist apart from “the rest of the week?”

One group of congregants—comprised of both Contemporary and Traditional members—preferred continuity between music heard on Sunday morning and throughout the week. I refer to this as musical immanence because the sounds of worship encompass and manifest the everyday world “outside” of worship. This type of relationship to worship characterizes evangelicalism, which has been the main source of guitar-heavy Contemporary worship music. Most mainline Protestants who preferred musical immanence were Contemporary worshipers who regularly listened to Contemporary Christian Music and mainstream popular music outside of church. One praise band singer explained, “The music we do in the Contemporary service is music that I listen to. Not just because I’m rehearsing it or I’m singing it in preparation for something, but because I would choose to turn it on and listen to it.” As another worshipper put it, for her, music in church was just like “like what you’d sing in your car by yourself.”

A small proportion of Traditional service attendees reported the same desire for and experience of musical immanence. They described listening to classical music and sacred music—both of which included some organ—during the week, but these people were used to searching out their desired music on particular radio stations or recordings outside of mainstream media channels.

Most Traditional worshipers reported finding little resonance between Sunday morning’s music and the rest of their sonic week. They usually went on to explain that this was a good thing. These congregants wanted musical transcendence, with worship sounding different than the rest of the week. For them, the sounds of worship transcended mundane experience to demarcate a sacred time and place, a sanctuary. Pipe organs provided a welcome counterbalance to the readily available commercial music these worshippers were usually exposed to during the week.

These two approaches of musical immanence and transcendence help explain why congregants found the two sides of the Worship Wars dichotomy to be so incompatible. When mainline churches supported both styles of music, they were supporting fundamentally different approaches to worship and relation with the divine.

Deborah Justice teaches at the Setnor School of Music at Syracuse University and is Managing Director of the Cornell Concert Series at Cornell University. She is the author of Middle Eastern Music for Hammered Dulcimer.