New York Farm Workers Gain 40 Hour Work Week

Guest post by William Scheuerman

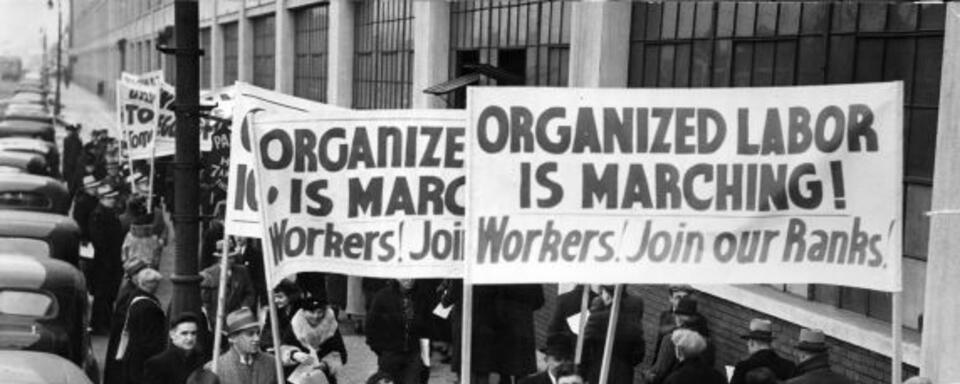

In my most recent book, A New American Labor Movement: The Decline of Collective Bargaining and the Rise of Direct Action, I document how tens of thousands of non-union workers are improving their terms and conditions of employment through militant political action rather than at the bargaining table. The recent announcement by New York’s Labor Commissioner to phase in a forty-hour farm laborer work week is a good example of this trend.

Let’s put this in context. Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal, which helped lift industrial workers out of poverty, excluded farmworkers. The National Labor Relations Act (NLRB) gave workers the right to form unions; the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) set a federal minimum wage, provided for weekly maximum hours, and prohibited child labor; and the Social Security Act (SSA) as originally passed provided workers with unemployment compensation and pensions. Senators from the south whose votes Roosevelt needed to pass these bills refused to support them unless they excluded farm and domestic workers, most of whom were people of color. Faced with the choice of excluding domestics and farmworkers or not having any of the bills passed, Roosevelt accepted this racist driven compromise.

As my chapter on farmworkers explains, the consequences for them were devastating. Without the legal protections available to industrial workers, farmworkers worked long hours for less than minimum wage. They had no retirement benefits, or sick pay, and most were not even eligible for food stamps. Neither were they eligible for Medicare, Medicaid and financial assistance to dependents, the aged and the indigent, all benefits provided by subsequent amendments to the Social Security Act. Lacking occupational safety protections, farmworkers suffered a disproportionate number of injuries and were frequently exposed to hazardous chemicals. Sanitation facilities in the fields were virtually non-existent. Since pay was by piecework, it wasn’t unusual to see little children working the fields alongside their parents. Living mainly in overcrowded migrant camp housing, their living conditions usually lacked such basic amenities as a stove, a shower and warm water.

After decades of suffering through such terrible work conditions, New York farmworkers joined in a major movement for change in 1989. That was the year a coalition of religious, community and labor groups formed the Justice for Farmworkers (JFW) coalition. Spearheaded by the Rural and Migrant Ministry (RMM), the coalition launched aggressive educational campaigns, farmworker marches and demonstrations, and intense political lobbying of the state’s leading politicians. Over the years, it made gradual gains for the farmworkers, improving safety and sanitary conditions. (See Chapter 3 for a detailed list of gains.) But the big victory came in 2019 with the passage of The Farmworkers Fair Labor Practices Act, which set the work week at sixty-hours, established a wage board, prohibited strikes, but gave farmworkers the right to unionize, and covered farmworkers under the New York state minimum wage law.

The last issue to be resolved was overtime pay. The political coalition set its sights on reducing farmworkers work week to forty hours, as the case with industrial workers. Thanks to the continued activism of the JFW, in early Fall of 2022 the wage board recommended establishing a forty hour work week. Claiming that the new overtime pay rules would force many farms out of business, the New York Farm Bureau opposed vociferously, as did many farmers and the Republican candidate for governor. But they lacked the political clout to stop the change. On February 24 Governor Hochul’s Labor Commissioner issued an order to phase in a forty-hour work week by 2032.

The story of New York farmworkers illustrates that taking political action can be an effective alternative to collective bargaining for gaining workers’ rights. As of this writing, only 12 New York farmworkers out of 56,000 are unionized. But unions played a crucial role in the coalition that achieved these political gains. In the past year, headlines have trumpeted the success of Amazon and Starbucks workers in forming unions, but what goes underreported is the larger role of unions in supporting and mentoring workers outside of collective bargaining.

William E. Scheuerman is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at the State University of New York at Oswego. Prior to retiring as President of the National Labor College, he served as President of the United University Professions, the faculty and staff union at SUNY. He is currently Treasurer of the American Labor Studies Center. Scheuerman has authored several books, including United University Professions: Pioneering in Higher Education Unionism (with Nuala McGann Drescher and Ivan D. Steen), also published by SUNY Press.