Why Write a Memoir?

Guest post by Laura Waterman

If we write to gain an understanding of ourselves, memoir is the form in which such writing can take place.

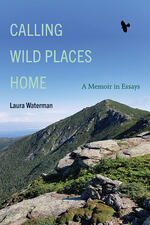

In my memoir, Calling Wild Places Home, I devoted an essay to how making one phone call changed my life. This, at the time, I couldn’t have seen. I was much too wrapped up in my daily life to see how becoming a rock climber—and everything that came from that—evolved from a relatively casual decision to pick up the telephone and call to register for the Appalachian Mountain Club’s program for beginner rock climbers.

Memoir writing can be about those pivotal events that lead you into a greater understanding of your life.

But here’s the catch. Here’s the great thing about memoir. What made me make that call? Here’s where the real work begins. For me, I had recently returned from a months-long trip and found myself unable to pick up my old life in the city again. I was looking for a way out, though I was hardly aware of this. At that point, just getting out of the city on weekends sounded good to me. And then what happened? That’s how we memoirists start, as we say, “peeling the onion.”

In writing memoir we are given the chance to engage with ourselves at a deep level. We can take a “backward glance,” as Edith Wharton titled her autobiography. This great writer was not writing a memoir, but I’ll use her evocative phrase to serve as a stepping-off point for memoir writers. I’ve come to think of memoir writing as a “backward glance,” plus. For me the plus means this backward glance can become a scrutiny, a microscopic examination, an exercise in a form that has the power to change our lives. Writing memoir puts us on the path to focus on events that have, for better or worse, shaped us. Through writing memoir, we gain an understanding of the mechanics of how that shaping happened. We gain self-knowledge. We learn who we are.

Of course, we will never discover ourselves completely because we are always being changed by the daily experience of our living. We are like the onion: another fold is beneath the one just peeled. You can keep on peeling until a tiny invisible center is left. That could be peeled too, if you had the tools for it.

Memoir writing gives us those tools. The hardest part is to begin.

The interesting thing about this peeling—of the onion, of your own inner core of emotions and often tangled thoughts—is that with every layer peeled you gain. Memoir writing is pure gain. It’s highly personal. You are confronting your past. By doing so you risk evoking thoughts, or scenes, that can cause pain. But if you stick with it, the pain eases. It’s not gone. It’s just waiting for you to return, with pen and paper in hand, to keep peeling. It might feel never ending, but every revision gets you closer, deeper into an understanding.

Yes! That “backward glance plus” can turn into hard work. Scary work. When we touch these memories they can burn our fingers. You shy back, pull away. You bury those pages in a deep dark drawer. But, ah! You can’t help yourself. Despite your stinging fingers you’re compelled to pick up your work again. You might battle back and forth, but at some point you get caught up in what you’re discovering. It feels true. And the other side of that is, you’ll know when it’s not true. You’ll feel yourself cringe, when you read over your work, if you’re lying to yourself. Or even if you’re just skimming the surface. And that is because you’re dealing with emotions, and emotions never lie. Memory cannot be trusted, but the emotions contained in the memory don’t change. Emotions can be complex and confusing, but they speak the truth. There is an emotional truth to events that we disregard at our peril, and it is the grist in the memoirist’s mill.

With my first memoir, Losing the Garden, I wrote five or six drafts that went no deeper than the first two or three peels of that onion. What made me find the courage to continue? The subject was my husband’s choice to take his own life. I was finding that to continue on with mine I needed to find out who I was, particularly why I morally supported his decision. Now I was on the right path—true and honest. It took a good half dozen more drafts.

This new memoir, Calling Wild Places Home, is another attempt at a scrutinizing “backward glance” from twenty plus years after my husband’s death. There is always more to discover. With the passage of time we learn about how past events can affect and change us. That’s the glory of writing memoir! We’ve hit our stride when we commit to the form that can not only bring healing but joy as well. Have I come to the end? Have I finished the job? Oh, no! We are always growing and changing. Our emotions, if we let them, will be our true guide, our lodestone.

We are writing to explain ourselves to ourselves. I believe that even if we choose not to publish our work, an act of sharing takes place: we have become more human—more ourselves—in the course of gaining self-understanding.

Laura Waterman is the author of Losing the Garden: The Story of a Marriage and Starvation Shore: A Novel. With her husband, Guy Waterman, she maintained the Franconia Ridge in the White Mountains of New Hampshire for almost two decades and was awarded the American Alpine Club's 2012 David R. Brower Award for outstanding service in mountain conservation. Together, she and Guy wrote numerous articles and books on the outdoors, including The Green Guide to Low-Impact Hiking and Camping; Wilderness Ethics: Preserving the Spirit of Wildness; Yankee Rock & Ice: A History of Climbing in the Northeastern United States; and A Fine Kind of Madness: Mountain Adventures Tall and True. In 2019, SUNY Press published the thirtieth-anniversary edition of their book Forest and Crag: A History of Hiking, Trail Blazing, and Adventure in the Northeast Mountains. Laura lives in Vermont.