‘Holy Incel, Batman!’ (Part 1)

Post-9/11 Sexuality and White Nationalism in Matt Reeves’ The Batman (2022)

Guest Post by Fareed Ben-Youssef (SUNY Press Author)

A No Jurisdiction Film Review

At a recent University of Warsaw talk for my newly released book No Jurisdiction: Legal, Political, and Aesthetic Disorder in Post-9/11 Genre Cinema, a student brought up Matt Reeves’ The Batman (2022) in the Q&A. My talk presented the introductory chapter which justifies why, to understand a cultural trauma like 9/11, we need to look at metaphorical representations of the attacks. And to fully grasp the costs of 9/11 and its ensuing wars, we need to look at our cinematic (super)heroes.

Riffing off the discussion, one of the students in attendance detailed some of the 9/11 iconography in the latest Batman movie which, in addition to directing, Reeves co-wrote with Peter Craig. The student pondered a sequence featuring the tower where the hero lives which is scarred by an explosion late in the film. I must confess that I fell into a happy tizzy as I saw others do No Jurisdiction-style interpretations!

No Jurisdiction is not only meant to serve as an account of genre movies past, but it is also meant to be a guide, a lens through which to see how trauma’s shadow looms over the spectacles we so eagerly take in while munching on popcorn. To see this more clearly, I suggest we explore movies not featured in the book that have recently or are currently screening in our cinemas. And as a lifelong fan of all things Caped Crusader, I can’t think of a better place to start our blog series than with a dive into The Batman, a movie haunted by a 9/11-like catastrophe.

At first glance, The Batman offers a classic tale of Batman (Robert Pattinson) heroically battling the supervillain, The Riddler (Paul Dano), who terrorizes the city through murder and larger acts of violence. However, when seen through the character’s history of sexual non-normativity and writings on the links between misogyny and white supremacy, a more surprising film emerges. The Batman offers a compelling portrait of a traumatized post-9/11 sexuality as it presents a potentially repressed superhero grappling with the threat of white nationalism and his own complicity in such movements. Through the leering and increasingly terrified eyes of the superhero, we can begin to see how the white, “lone wolf” terrorism that continues to afflict the United States is rooted in part within a toxic masculinity that views women with contempt. As Batman’s sidekick Robin might exclaim, “Holy Incel, Batman!”

Part 1 – A Sometimes Kinky, Sometimes Abstinent Superhero: Batman, Sexuality, and the Trauma of 9/11

To better understand the traumatized sexuality of Reeves’ Batman, it is helpful to linger on the superhero’s long-established link to nonnormative sexualities in both the comics and on the silver screen. In 1954’s Seduction of the Innocent, an exposé on how comic books warped vulnerable young minds and contributed to rising trends in juvenile delinquency, psychiatrist Fredric Wertham critiqued superheroes as fascist icons. Additionally, for Wertham, these supermen offered children laudatory examples of “abnormal” sexual behavior. Batman is targeted for his relationship with his young sidekick and ward, Robin. Wertham writes, “[o]nly someone ignorant of the fundamentals of psychiatry and of the psychopathology of sex can fail to realize a subtle atmosphere of homoeroticism which pervades the adventures of the mature ‘Batman’ and his friend ‘Robin’” (Wertham 189 - 190). He further asserts that the “Batman type of story may stimulate children to homosexual fantasies, of the nature of which they may be unconscious” (Wertham 191).

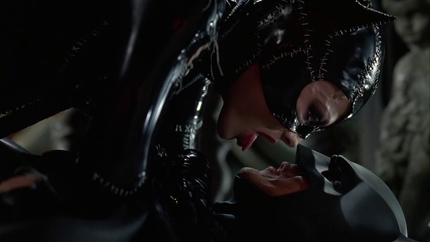

Reading the often-homophobic exposé attuned and appreciative to how superheroes can promote non-normative ideals, I find myself agreeing with the substance but not the tenor of Wertham’s assessment that superheroes can celebrate difference. To this point, he includes the extensive testimony of a “young homosexual” who found in the depicted closeness of Batman and Robin, not a paean to pederasty but a normalization of a loving, sexual relationship between those of the same gender (Wertham 192). The subject notes, “I remember the first time I came across the page mentioning the ‘secret bat cave.’ The thought of Batman and Robin living together and possibly having sexual relations came to my mind. You can almost connect yourself with the people. I was put in the position of the rescued rather than the rescuer. I felt I’d like to be loved by someone like Batman or Superman” (qtd. in Wertham 192) For some readers with non-normative identities, Wertham’s exposé shows despite itself that there is a utopian, even liberatory dimension to these tales. They showed readers who felt outcast that they were worthy of love. In my childhood, the non-normative sexuality of Batman was presented more explicitly and joyfully. Tim Burton’s Batman Returns (1992)—presenting the dalliances between a leather-clad Catwoman and a submissive Caped Crusader who she licks, straddles and whose skin she even penetrates with her claws—acts as a gleeful portrayal of a BDSM relationship (image below). Later, Batman pulls out one of her claws that was lodged in his side and, while admiring it, says to himself, “meow.” This Batman movie proved that our kinks are worthy of celebration.

For my part, I have been challenged to see how Batman offers a model of my own vexed sexuality. A friend once subtly critiqued my tendency to hide my romantic life, and heterosexuality, under a mask of asexuality by comparing me to the superhero in Eric Radomski and Bruce Timm’s animated film, Batman: Mask of the Phantasm (1993). Therein, the hero must choose between a happy and normative romantic life or his mask and his own obsessive mission. The mask and his mission win out. While her words stung, they pointed to how deeply my beloved superhero resonates with me. He offers me a reflection of a sexuality hidden under an all-encompassing (but not, I’d like to think, an inauthentic) mask.

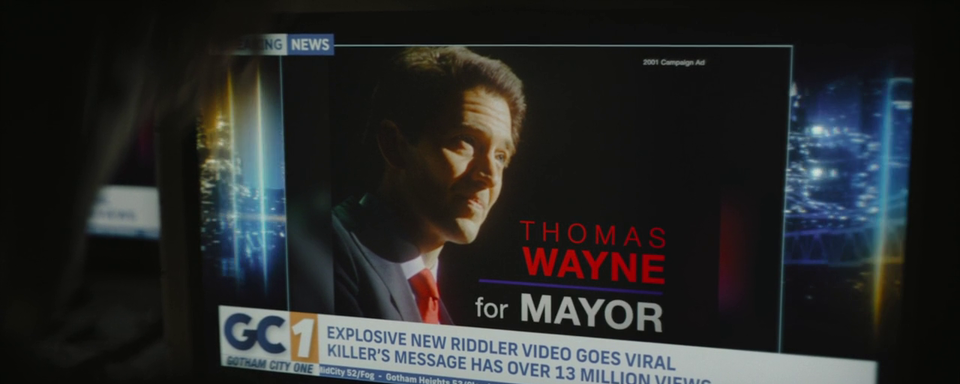

Whereas filmmakers like Burton relished a sexual and sexually playful Batman, Reeves’ Batman seems notably cut from a fully actualized sexuality. In some ways, Pattinson plays him as a child. As his alter ego Bruce Wayne, he tells his concerned butler with all the bitterness of an angsty youth, “You’re not my father!” In two separate scenes, Batman and Bruce Wayne are each stopped in their tracks by a boy whose father has just been murdered. The hero’s immobility in these moments of encounter with the bereaved child ties his psychic stasis to the canonical traumatic foundation of the Batman character—the death of his parents at the hands of a gunman. This typical feature of the character’s story takes on a particular political dimension in Reeves’ film when we learn that their death took place in 2001. The year can briefly be seen on the corner of the screen of a campaign ad where his father, Thomas Wayne, discusses his candidacy for mayor (image below).

Earlier, a newscaster notes that Thomas Wayne and his wife were killed shortly after he began said candidacy. Batman, or rather his defining quest for vengeance, was born during the year of the 9/11 attacks. He was born in a time of American crisis, too young to affect any change.

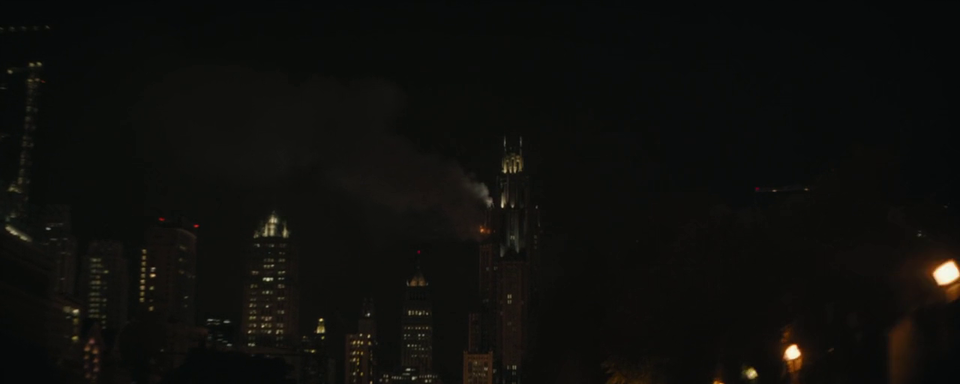

As we ponder a Batman born from a trauma that he could not prevent, one temporally linked to 9/11 and which stifled his expression and experience of intimacy, it is worth emphasizing that the attacks have been read as an attack on the phallic power of the United States. In an essay exploring post-9/11 masculinity, Bonnie Mann usefully describes the metaphoric significance of the footage of the World Trade Center attacks that was broadcast ad infinitum. For Mann, the imagery suggested the attacks resembled “a simultaneous act of penetration (the image of the towers being penetrated by the planes plays over and over again) and castration (the towers collapse)” (Mann 186). During its 9/11-like sequence featuring the burning tower, Reeves frames the Batman of the film as notably impotent. He speeds along in his usually impressive Batmobile to save the day only to be informed that he is about an hour too late. He’ll never be fast enough to stop the terrorist from attacking. A point-of-view shot presenting the edifice smoldering in the night sky is accompanied by the sounds of a boys’ choir (image below). Their falsettos resound over a reaction shot of a Batman looking up speechless—the music underscores this moment of shock and awe as one intertwined with boyhood. An emasculating 9/11-like trauma, one that shakes Gotham City and a wider nation, may keep this Batman trapped as an eternal adolescent.

It is through these forever-young eyes that he witnesses analogues for many traumas of post-9/11 America over the course of the film: from the flooded Super Dome of Hurricane Katrina-era New Orleans to the Charlottesville vehicular attack to violence against Asian Americans to (as we will discuss in Part 2 with the film’s Riddler) white nationalism and the incel movement. Our hero is not a savior of a nation; rather, in a moving metaphor for the true power these masked heroes hold for audiences, he acts as a masked witness of its dissolution.

Presenting a uniquely brooding yet petulant Batman, the film plays on Robert Pattinson’s star persona and his iconic turn as another character caught in an eternal youth. Pattinson’s 107-year-old vampire and high schooler Edward Cullen from the Twilight series was linked to the abstinence movement that was heavily supported and funded by the conservative Bush administration which oversaw 9/11 and the beginning of the ensuing War on Terror (Kelly 9). Pattinson pinpointed the importance of abstinence to the vampire’s appeal when noting, “The success of the Twilight books comes from the fact that fans can lust after Edward and yet, certainly in the first book, there’s no sexual contact between him and the series heroine. Twilight is a big metaphor for sexual abstinence, and yet its erotic underneath” (qtd. in Singh). Reeves sharply suggests, via the casting of an abstinence icon within a 9/11-tinged film, how abstinence culture and the War on Terror coalesced: Why choose sex when you could instead go fight the enemies that threaten our nation?

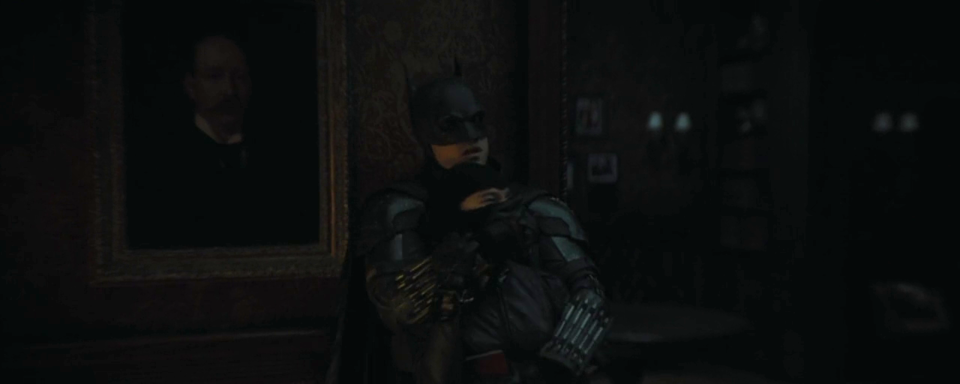

Just like Edward Cullen in the first book and film of Twilight, Pattinson’s Batman similarly abstains from sexual touch with his love interest, Catwoman (Zoë Kravitz). [Catwoman is always the one that initiates the few kisses between them.] Notably, Batman does engage her in combat and is comfortable putting his hand over her mouth to stifle her scream (image below).

He’s also comfortable watching her undress from the shadows. Catwoman herself jokes about the voyeuristic and non-consensual edge to the hero’s behavior when she asks, “Is that how you get your kicks, hon? Sneaking up on girls in the dark?” She also chastises him for using her as bait to garner further info on a crime plot along with his general apathy toward the fate of her missing friend. Indeed, while he resists actively touching the cat burglar outside of violent struggle, he is perfectly at ease telling her through an earpiece how she should move her body and, in a scene where he sees a nightclub through her eyes, how she should approach men. Here is a Batman of a particularly controlling type who uses the woman who attracts his gaze as an extension of his own body, as a tool. Gone is the submissive Caped Crusader of Batman Returns. In its stead is a Batman of repressed urges who aims to dominate a (Cat)woman. His traumatized sexuality, stemming from an emasculating cataclysm that he was powerless to stop, has trapped this Batman in a space where the only touch that makes sense is one applied with violence. Only once he sees how he reflects the most terrorizing of impulses will this Batman consider a new way of being with others.

Before we dive into Part 2 of this post about how Reeves’ Batman is connected to the Riddler—a villain with strong connections to white nationalism and the incel movement—let’s take a short break. While you await the second part of my review of The Batman, be sure to buy my book that features dozens more movies (including the entirety of Christopher Nolan’s The Dark Knight trilogy!) and ask your library to purchase a hardcover copy.

Works Cited

The Batman. 2022. Dir. Matt Reeves. Warner Home Video, 2022. Blu-Ray.

Batman: Mask of the Phantasm. 1993. Dirs. Eric Radomski and Bruce Timm. Warner Bros. Pictures, 1999. DVD.

Batman Returns. 1992. Dir. Tim Burton. Warner Brothers, 2010. Blu-Ray.

Kelly, Casey Ryan. 2016. Abstinence Cinema: Virginity and the Rhetoric of Sexual Purity in Contemporary Film. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Mann, Bonnie. 2008. "Manhood, Sexuality, and Nation in Post-9/11 United States." In Security Disarmed: Critical Perspectives on Gender, Race, and Militarization, edited by Sandra Morgen, Barbara Sutton, and Julie Novkov, 179 – 197. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Singh, Anita. 2009. “Twilight teaches teenage girls that abstinence can be sexy, says Robert Pattinson.” The Telegraph, November 28. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/culture/film/film-news/6672013/Twilight-teaches-teenage-girls-that-abstinence-can-be-sexy-says-Robert-Pattinson.html.

Wertham, Fredric. 1954. Seduction of the Innocent. New Yok: Rinehart & Company, Inc.