The North End, Un Paesano della Città

A Village in the City

Guest Post by Nicholas Dello Russo

Boston has always been a seafaring city. Its magnificent natural harbor embraces the coast, offering protection from the fierce North Atlantic storms. In 1630 John Winthrop and the Puritans sailed into Boston Harbor seeking religious freedom and called Boston “a city upon a hill,” echoing Christ’s Sermon on the Mount. Boston would become a beacon to the world and would welcome all people, no matter their status or background. Emma Lazarus, in her great poem, said the Statue of Liberty was the “Mother of Exiles.” In the 19th and early 20th centuries these exiles flocked to America, none more so than the Southern Italians.

At that time Italy was in chaos. The recently unified Northern Italian provinces prospered under the Savoy monarchs. The South, however, still existed in a feudal state, little changed since medieval times. The vast majority of Southern people were peasants, serfs who worked as day laborers or itinerant agricultural workers. The arable land was owned by wealthy absentee landlords who lived in the cities. The serfs were called terroni, people of the earth, and were considered backward and uneducable. These paesani knew their lives were hopeless and that the future held little chance of advancement for their children. In order to cope with their brutal existence they developed strategies that helped them survive. They became suspicious of outsiders and only congregated with their own families and friends. This attitude was called campanilismo, meaning an affinity for people who lived within the sounds of the town’s bells.

New York’s Ellis Island was the main port of entry for Italian and other immigrants, but Boston was the second most active landing port. The steamships from Europe landed either at the Cunard dock in East Boston or at Hoosic Pier in Charlestown. From there it was only a short walk or ferry ride to the North End, which was for a hundred years considered Boston’s Little Italy. The arriving Italians were poor and lived in squalid tenement buildings without central heat or hot water and with only a shared toilet bowl in the hallway. It was a desperately poor existence but it offered them something they never had in Italy, hope for the future, because here in la’merica they could find work and make money.

The twisted, narrow streets of the North End where once Yankee Puritans walked became home to thousands of Southern Italians. They, quite naturally, tried to duplicate their village life in the big city. They opened restaurants and coffee shops. There were butchers, greengrocers, Italian grocery stores, doctors, accountants and lawyers all catering to the needs of the nascent Italian community. Because the tenement apartments were small, street life abounded and the main streets, Hanover, Salem and Endicott streets, were alive with people at all hours. In the summer street festivals were held honoring favorite village saints.

The people who lived in the Italian North End loved their village life, but the 20th century intruded. In the mid 1970s gentrification began nibbling at the edges of the North End. It started along the waterfront where the dilapidated piers were turned into luxury condominiums. Real estate agents opened offices in a neighborhood where traditionally apartments were rented and buildings sold by word of mouth. Italians began moving to the suburbs and young, urban professionals moved into the newly renovated apartments.

Yet, the warmth and character of the old North End lingers on. There are still Italian restaurants, coffee and pastry shops. Former North Enders return to visit family, have a cappuccino, and play bocce with old friends. Times change but the spirit lives on.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------

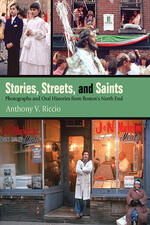

Nicholas Dello Russo wrote the foreword for Stories, Streets, and Saints

"I was born one month before the end of World War II. My father, Jerry, was a soldier in the US Army and my mother, Emily, was the secretary for the director of the North End Union, a local settlement house. They had no health insurance so I was born in the charity ward of the Massachusetts General Hospital, the same hospital where I’ve worked for the past twenty three years.

We lived in a cold water flat on Salem Street, four tiny rooms without central heat or hot water. At that time there were still horse-drawn wagons delivering meat, produce, and ice from the market at Faneuil Hall to the retail shops on Salem Street. I was educated through high school at local parochial schools and then at Boston College and Tufts University.

My grandparents emigrated from hill towns in southern Italy in the late 19th century and entered America through Ellis Island. Between them they had eighteen children all of whom had typical immigrant jobs; barber, bartender, seamstress, candy dipper, salesgirl, undertaker, and bookmaker.

Six generations of my family have lived in the North End of Boston. I’ve watched the neighborhood change from a poor tenement district to an upscale tourist destination with expensive restaurants and coffee shops.

The story of the North End is the story of America. In The New Colossus, Miss Liberty asked Europe to send, “your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” and the southern Italians responded enthusiastically to the kind invitation.

This book, Stories, Streets and Saints, tells their simple stories and celebrates their quiet lives."